The Man Who Invented AGI

The phrase hangs in the air of every tech conference, boardroom, and late-night coding session: Artificial General Intelligence. AGI. It is the north star of Silicon Valley, the holy grail of computation, the theoretical end-point where machines no longer just perform tasks but possess the cognitive abilities of a human being. AGI represents the moment when an AI can reason, learn, and create across any domain, matching or even wildly surpassing our own intellectual capabilities.

This pursuit has become the engine of the modern economy. The world’s most powerful corporations are locked in a relentless race to achieve it. Recent headlines are a testament to its gravity: a landmark deal between Microsoft and OpenAI hinges on the very definition of what happens when AGI is reached. Tech giants like Meta, Google, and Microsoft are funneling unprecedented massive capital expenditures into its development. The insatiable demand for the computational power to chase AGI has propelled companies like Nvidia into the stratosphere, becoming a $5 trillion company. The geopolitical stakes are just as high, with US politicians framing the race for AGI as a national security imperative against China.

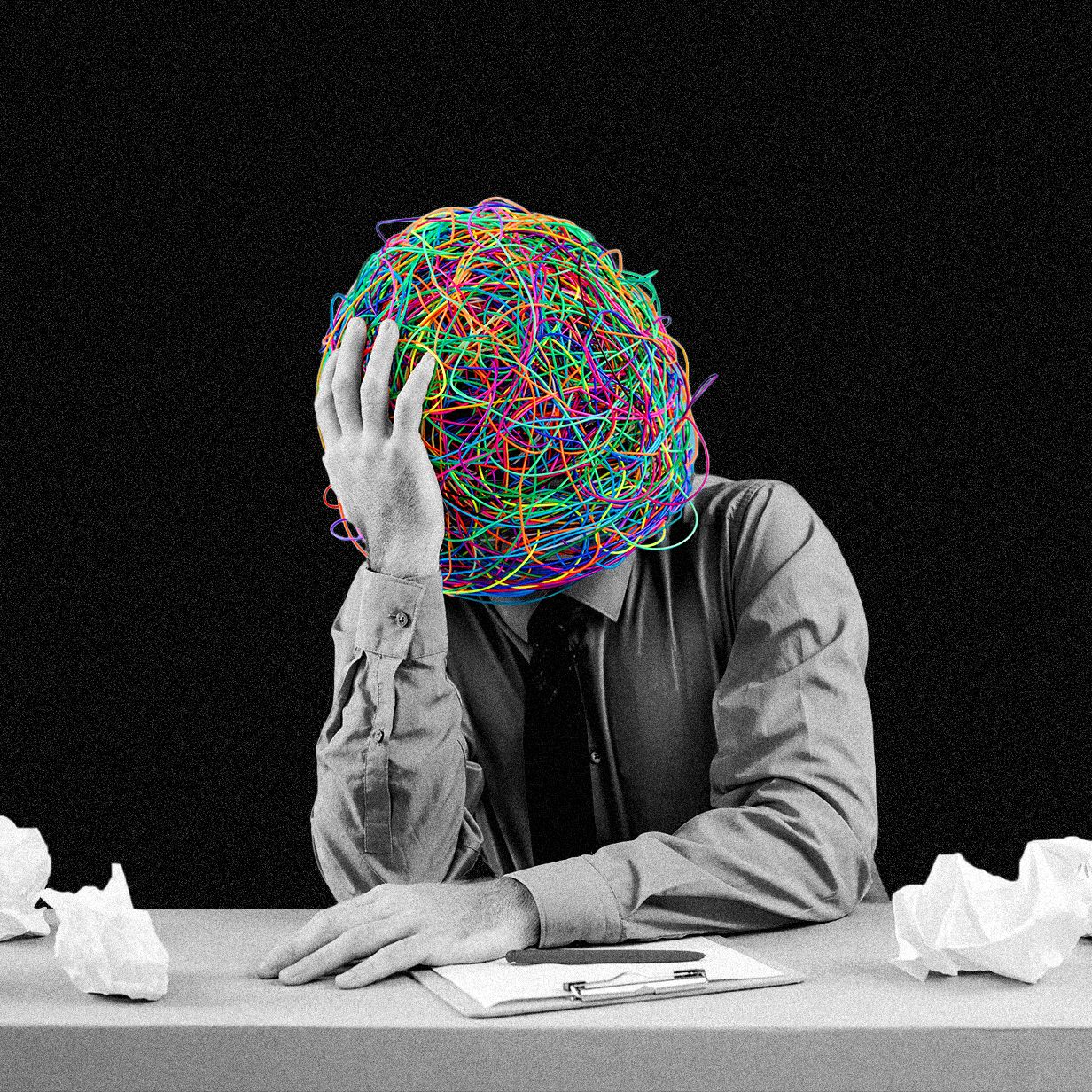

As prognosticators claim we might reach this monumental milestone before the end of the decade, the term AGI has become ubiquitous. It’s an acronym that represents both utopian promise and existential dread. Yet, for all its power and influence, the origin of this pivotal term remains shrouded in obscurity. Who first stitched together “artificial,” “general,” and “intelligence” to name the very concept that now defines our future? The answer lies not in a famous corporate lab or a prestigious university department, but with a lone academic whose story is as compelling as the technology he named.

A Ghost from the Past: The Dawn of AI

To understand the birth of AGI, one must first travel back to a time before the term existed, to the very genesis of its parent field. In the sweltering summer of 1956, a small, visionary group of academics convened on the quiet campus of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. In an era of vacuum tubes and punch cards, they gathered to embark on a quest that seemed torn from the pages of science fiction: to create machines that could think.

This legendary meeting, now known as the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, was the crucible where the field was formally born. It was here that one of the organizers, John McCarthy, coined the foundational term “artificial intelligence.” The ambition of these pioneers was not to build narrow systems that could only play chess or solve specific mathematical problems. Their vision was grand and holistic. They dreamed of creating machines with the full breadth of human cognition—systems that could use language, form abstractions, and improve themselves in a world they were just beginning to understand. In essence, the original dream of AI was what we would now call AGI.

However, the decades that followed saw this grand vision fragment. The immense difficulty of creating genuine machine cognition led researchers down more practical, narrower paths. The field entered a period of specialization, focusing on what became known as “weak” or “narrow” AI. These systems excelled at specific tasks, leading to the development of expert systems in the 1980s and, eventually, the machine learning algorithms that power much of our modern world. While undeniably useful, this was a far cry from the Dartmouth dream. The pursuit of a truly general intelligence was largely relegated to the fringes, and the field endured a long and punishing “AI Winter,” where funding dried up and progress seemed to stall. The original, sweeping ambition of AI had been lost, and the term itself had come to mean something much more limited.

The Unsung Prophet of a New Age

While the mainstream AI community was grappling with the challenges of expert systems in the late 1990s, a graduate student named Mark Gubrud was preoccupied with a different set of future-facing anxieties. Gubrud was an enthusiast of nanotechnology, the science of manipulating matter at the molecular level, popularized by the visionary engineer Eric Drexler. But his fascination was tinged with deep concern. He saw the potential for these powerful, nascent technologies to be weaponized, creating new and terrifying instruments of war.

“I was a grad student sitting in the sub-sub basement at the University of Maryland, listening to a huge sump pump come on and off very loudly, right behind my desk, and reading everything that I could,” Gubrud recalls from a cabin porch in Colorado. His research wasn’t just about the technology itself, but its intersection with global security and the very nature of conflict.

In 1997, this deep-seated concern culminated in a paper he presented at the Fifth Foresight Conference on Molecular Nanotechnology. Titled “Nanotechnology and International Security,” his work was a stark warning. He argued that emerging breakthrough technologies would redefine warfare, potentially leading to catastrophes far exceeding the horrors of the nuclear age. He made an impassioned plea for nations to “give up the warrior tradition” in the face of these new perils.

Buried within this prescient paper was a novel phrase. To distinguish the kind of powerful, human-level intellect he was worried about from the limited “expert systems” of the day, Gubrud needed a new descriptor. He wrote of nanotechnology, of course, but also of advanced AI, which he referred to as “artificial general intelligence.” It appears to be the first documented use of the term. Later in the paper, he offered a definition that remains remarkably relevant today:

“By advanced artificial general intelligence, I mean AI systems that rival or surpass the human brain in complexity and speed, that can acquire, manipulate and reason with general knowledge, and that are usable in essentially any phase of industrial or military operations where a human intelligence would otherwise be needed.”

If you remove the final clause about military operations, you are left with the core definition of AGI that industry leaders and researchers use today. “I needed a word to distinguish the AI that I was talking about from the AI that people knew at the time,” he explains. “It was pretty clear that was not going to be the kind of general intelligence they were.”

Despite its foresight, Gubrud’s paper had minimal impact. It was presented to a niche audience, and the term “artificial general intelligence” faded back into obscurity, an intellectual seed planted in barren ground, waiting for the right conditions to sprout.

A Term Reborn from the Ashes of Winter

As the 20th century gave way to the 21st, the chill of the AI Winter began to recede. A few perceptive researchers sensed a coming thaw. In his 1999 book, The Age of Spiritual Machines, futurist Ray Kurzweil boldly predicted that AI would achieve human-level cognition by around 2030. This idea resonated deeply with computer scientist Ben Goertzel, who, along with his collaborator Cassio Pennachin, began compiling a book dedicated to exploring pathways toward this more ambitious form of AI.

The group faced a familiar semantic problem: what to call this concept? The original term, “AI,” had become synonymous with narrow applications. Kurzweil had used the phrase “strong AI,” but it felt ambiguous and ill-defined. Goertzel experimented with alternatives like “real AI” and “synthetic intelligence,” but none of them captured the essence of their pursuit or resonated with the book’s contributors.

He opened the floor to suggestions, sparking an email discussion among a group of thinkers who would become major figures in the field, including Shane Legg, Pei Wang, and Eliezer Yudkowsky—the man who would later become the doomer-in-chief of AI existential risk.

It was Shane Legg, then a master’s graduate who had worked with Goertzel, who proposed the solution. As he recalls it now, “I said in an email, ‘Ben, don’t call it real AI—that’s a big screw you to the whole field. If you want to write about machines that have general intelligence, rather than specific things, maybe we should call it artificial general intelligence or AGI. It kind of rolls off the tongue.”

The suggestion clicked. Pei Wang, another contributor, apparently suggested a different word order—general artificial intelligence—but Goertzel noted that its acronym, GAI, might carry an unintended and distracting connotation. They settled on Legg’s proposal: AGI.

| Key Figure | Contribution to the term “AGI” | Impact & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Mark Gubrud | The Originator: First coined and defined “artificial general intelligence” in a 1997 academic paper. | His work was ahead of its time and focused on the security risks of AGI. It went largely unnoticed for years. |

| Ben Goertzel | The Popularizer: Led the effort in the early 2000s to find a new name for human-level AI, ultimately adopting and promoting AGI. | Organized the community and edited the book that helped cement AGI in the modern lexicon of AI research. |

| Shane Legg | The Reinventor: Independently proposed the term “artificial general intelligence” during an email discussion with Goertzel’s group. | His suggestion was the one adopted by the community. He later co-founded Google DeepMind, becoming its chief AGI scientist. |

Pei Wang, now a professor at Temple University, reflects that the term they settled on in 2002 was essentially a return to the roots of the field. “Basically, the original AI,” he says, was what the Dartmouth founders had envisioned. “We needed a new label because the only one had changed its common usage.”

The die was cast. “We all started using it in some online forums, this phrase AGI,” says Legg. The term began to spread through the small but dedicated community of researchers focused on this grander vision. Even though Goertzel’s book, aptly titled Artificial General Intelligence, wasn’t published until the middle of the decade, the acronym had already begun its ascent, eventually spawning its own dedicated journal and conference.

An Inventor’s Unclaimed Legacy

It wasn’t until the mid-2000s, as the term AGI was gaining momentum, that Mark Gubrud’s original contribution came to light. He himself brought his 1997 paper to the attention of the community that was now championing the term.

The reaction was one of surprise. “Somebody pops up out of the woodwork and says, ‘Oh, I came up with the term in ‘97,’ and we’re like, ‘Who the hell are you?’” Legg remembers. “And then sure enough, we looked it up, and he had a paper that had it. So [instead of inventing it] I kind of reinvented the term.” Legg, now the cofounder and chief AGI scientist at the formidable Google DeepMind, readily acknowledges Gubrud’s precedence.

Gubrud attended the second AGI conference in 2006, where he briefly met Goertzel. Though he never met Legg in person, their online interactions over the years have always been friendly. Gubrud is philosophical about his place in the history books, understanding that his lack of follow-up allowed him to be edged out of the narrative he unknowingly started.

“I will accept the credit for the first citation and give them credit for a lot of other work that I didn’t do, and maybe should have—but that wasn’t my focus,” he says. His primary motivation was never to name a burgeoning field but to sound an alarm. “My concern was the arms race. The whole point of writing that paper was to warn about that.”

True to his original mission, Gubrud’s subsequent work, though not prolific, has consistently centered on the dangers of advanced technology. He has authored papers arguing for a ban on autonomous weapons and continues to advocate for caution in the face of rapid technological advancement.

The dissonance between his life and the global phenomenon he named is impossible to ignore. “It’s taking over the world, worth literally trillions of dollars,” Gubrud reflects. “And I am a 66-year-old with a worthless PhD and no name and no money and no job.”

Yet, Mark Gubrud does have a legacy, one that is becoming more critical by the day. He gave a name to the most ambitious technological pursuit in human history. His definition, conceived in a basement office nearly three decades ago, still holds. And his warning—that the creation of such a powerful intelligence is fraught with peril and demands profound ethical consideration—is a message that echoes louder and more urgently than ever before. He may not have built the AGI industry, but he was the first to see it coming and give it a name. The question that remains is whether the world he inadvertently helped label will ever truly listen to his warning.

Comments